Parque Jotache (JH Park)Julio Herrero Guisado (1898-1986)

Extant

Torrelodones, Community of Madrid, 28250, Spain

The site is easily accessible and free to public strolling and viewing.

About the Artist/Site

Julio Herrero was born in Toro (Zamora), the oldest of four sons of a family of subsistence farmers. He was schooled by the members of the Piarist religious order, a group dedicated to the education of poor children, and he particularly excelled in line drawing and writing, while also serving the order as an altar boy. At age twelve he accidentally dislocated his right elbow; rather than taking him to a doctor, his parents brought him to a traditional healer who botched the realignment, thus leaving him partially disabled. With no expectation of being able to stay on the land and remain a farmer as a result of this disability, Herrero’s grandmother paid for a train ticket for him to travel to Madrid, sending him off with no money and no fixed destination. His very first day he inquired for work at every business that he passed and found an apprentice position at a local firm that sold fabrics and ready-to-wear goods. He was to remain in this line of work his entire life.

Around 1934, Herrero began purchasing land in the small town of Torrelodones, located approximately 18 miles northwest of Madrid. Nestled in the southern foothills of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range, the town is crossed by a fault line, the geological consequences of which have resulted in widespread outcroppings of granite in this otherwise low-lying basin. Between 1935 and 1967, Herrero ultimately pieced together approximately 11.5 acres of land that, although primarily flat, were rocky and pierced by numerous granite boulders. In fact, one of the acquisitions, in 1953, was earmarked for a quarry; another, in 1956, provided him with a three-quarter acre parcel on which he built a two-story house, taking advantage of the boulders found in close proximity. Herrero used these lands as collateral for building up his business; with more land, he was able to receive more credit from the banks and, with help from his wife and his three children, he ultimately developed the factory into the prosperous company, now known as Jotache Prolab, S.A., that the family still runs today. In the 1970s he developed a plan for the Torrelodones property to construct six single-family dwellings—one for each of his three children and three others to rent—surrounding a central park that included plans for a swimming pool, various paths and walkways, and stone amenities such as picnic tables and outdoor shelters. He called this park El Peñon [The Boulder], after the original name of the part of the property on which he built his house. However, because the majority of the estate had been parceled off for the homes, the section available for the central park was reduced to just under two acres.

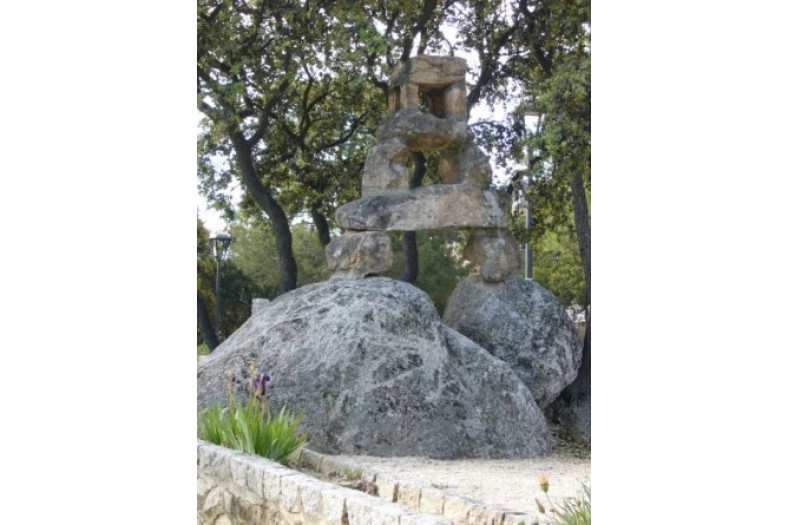

Nevertheless, his ideas for the park area were creative and intriguing; he played off the natural formations, supplementing them with the materials he trucked onto the site to create a variety of formalist, functional, and representational works. He seemed particularly interested in the water elements, and devised ponds, wells, and channels to naturally irrigate the pine, cypress, cedar, oak, and plum trees that he planted. But even these components are unusually and often elaborately formed, with idiosyncratic stone work that goes far beyond the functional requirements. Much of the work is bulky and monumental, with slabs and posts recalling megalithic, spiritual structures such as dolmen, and rounded zoomorphically-shaped stones clearly reminiscent of such carvings as Castilla y León’s famous Guisando bulls (fourth century b.c.e. to third century c.e.). In addition, much of the work also reveals an amusing aspect: the juxtaposition of varying kinds and shapes of stones within a single element, even those simple as a post.

Meanwhile, the little town of Torrelodones was growing considerably, doubling its population each decade from 1970 to 2010. The new city officials saw their role as town leaders differently vis-à-vis their citizens than did those of Franco’s government, and were enthused about adding educational and social services to support their growing population. They were also particularly concerned about the lack of parkland, so early in 1980 approached Herrero with a proposal to trade the El Peñon site for other grounds owned by the city. At age 82, Herrero finalized the agreement, and the city became the owner of all of Herrero’s stone sculptures and amenities, as well as the house and grounds. The new Parque JH, renamed to honor Herrero, was officially blessed and opened to the public in April 1981, and immediately began a program of exhibitions, conferences, and meetings within the new center.

After the initial momentum, however, the Torrelodones administration drew back from big projects and retreated to a modest maintenance program, so that during the next twenty years there was little genuine improvement or proactive exploration into ways the park could better serve the community. By March 2009, however, a new series of installations were unveiled, including hanging bridges, archery, scaling walls, and more. Although perhaps the major draw of Parque JH now is not the stone work, the fact that it is now actively used by a broad-based public can only serve to enhance the maintenance of those early works as well. It is easily accessible and free to public strolling and viewing.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2014

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Torrelodones, Community of Madrid, 28250

es

Latitude/Longitude: 40.5766078 / -3.9293646

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.