Das JunkerhausKarl Junker (1912)

Extant

36 Hamelner Straße, Lemgo, Nordrhein-Westfalen, 32657, Germany

Today Junker's house has become a museum, and visitors are welcomed in an annex building, which has a display of Junker's visual art and is linked to the original house with a glass corridor. However, to protect the fragile wooden structures, not all rooms within the building are open to the public.

About the Artist/Site

Karl Junker was born August 30, 1850 in Lemgo, a small German city in the Lippe district of North Rhine-Westfalia. Lemgo, which was founded at the end of the twelfth century, has retained much of its historical character, as it was not bombed during World War II.

At a very young age, Junker successively lost his mother, younger brother, and father, and so, an orphan by age seven, he was educated by his grandfather. In 1869 he moved to Hamburg for a couple of years to learn the carpenter’s trade. There, a love affair with the daughter of his teacher went wrong, and in1871 the young man moved on to Munich.

His whereabouts and occupation during the next few years is unclear, but in 1875 Junker enrolled in Munich’s Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Visual Arts). After finishing his academic studies in 1877, he began a trip of some three or four years throughout Italy, in this way completing his artistic education by visiting famous cities such as Florence and Venice. Those drawings of his that survive from that period primarily represent architectural images.

In 1881 he returned to Germany. A young man in his early thirties, he was no doubt eager to obtain a position in the world of arts. It is known that in 1883 he returned to live in Munich, but his whereabouts during 1881-83 are once again unclear.

By 1887 he had moved back again to Lemgo, and in October 1889 he submitted an application to the local authorities to build a house of his own design. He was able to afford to do so because he had received a significant inheritance following the death of his grandfather; these funds would last him for the rest of his life.

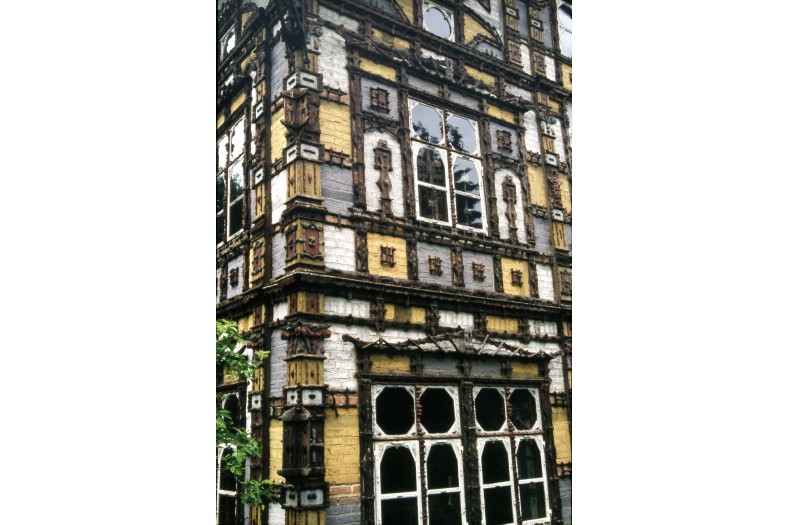

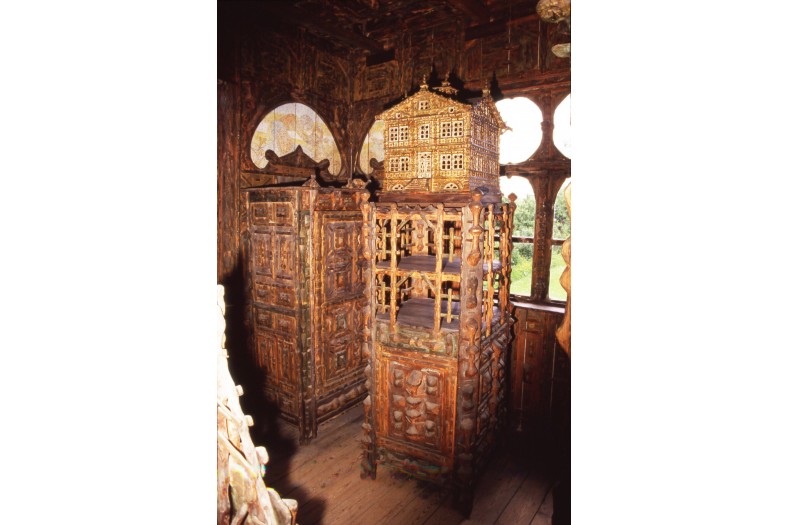

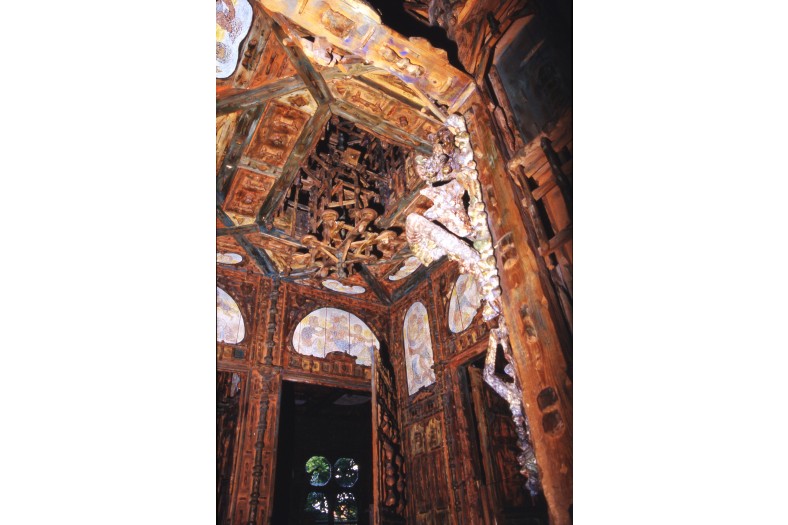

Junker designed a two-storey house with a square base, and each of its four identical half-timbered sides has a gable roof. In the center of the roof is a small square belvedere surrounded with glass windows. The construction of the house was completed in March 1891, and, although not documented, it is plausible that immediately thereafter Karl Junker started decorating and finishing his residence, which was a project that would occupy him until his death over twenty years later.

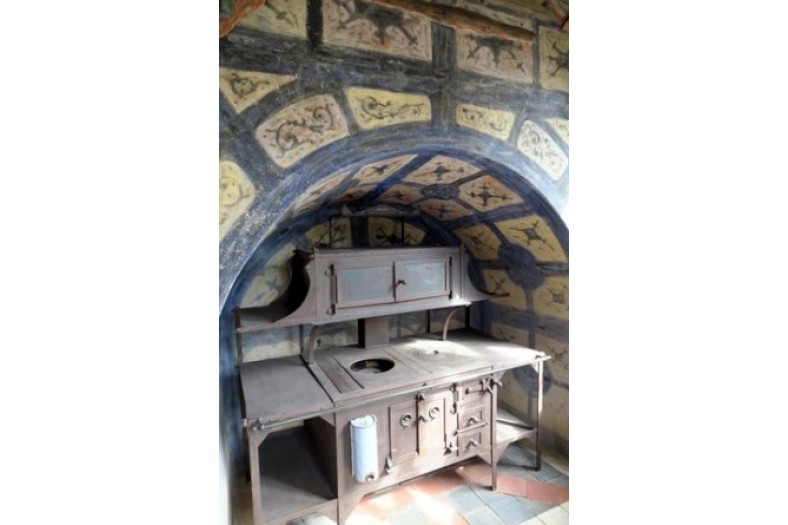

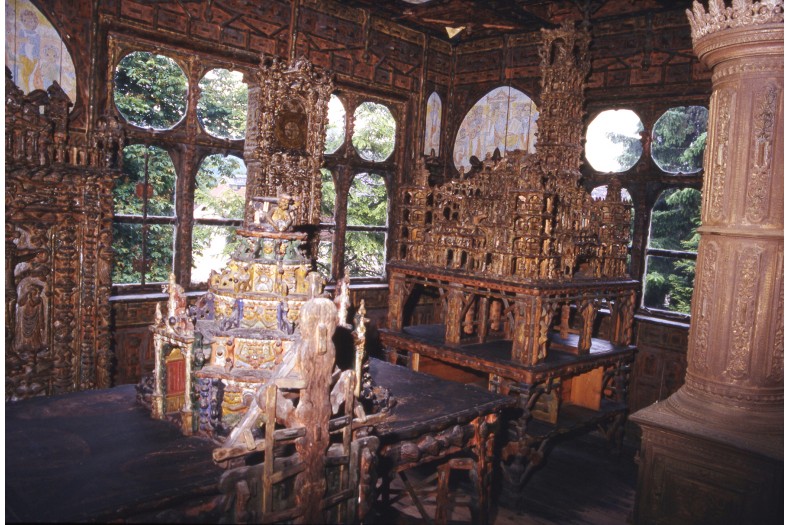

The ground floor has a vestibule, a kitchen, a storeroom, and other rooms with a practical function; the second floor has the living room with annexed salon, a master bedroom, a children's room, and a guest room; the third floor has two more bedrooms and a third room that served as a study or servants’ room, and from which rose a staircase to the belvedere. The footprint and arrangement of the house fit the usual format of a German middle clas dwelling of that era; nothing seemed special or extraordinary at the beginning.

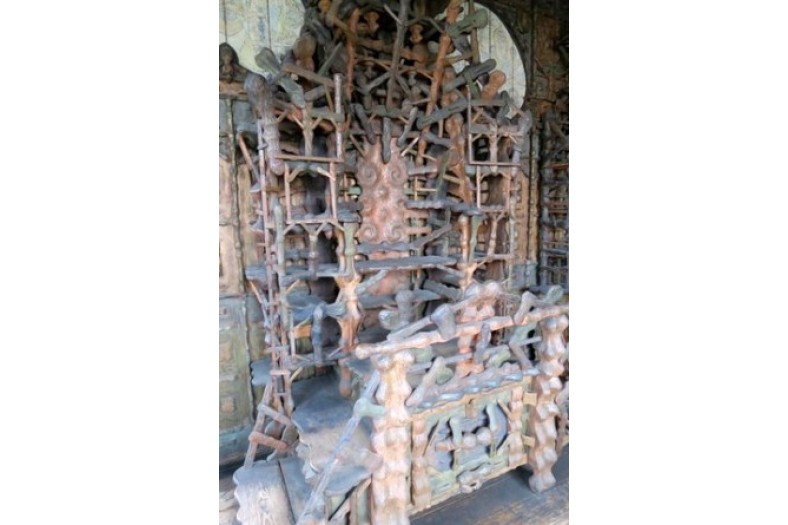

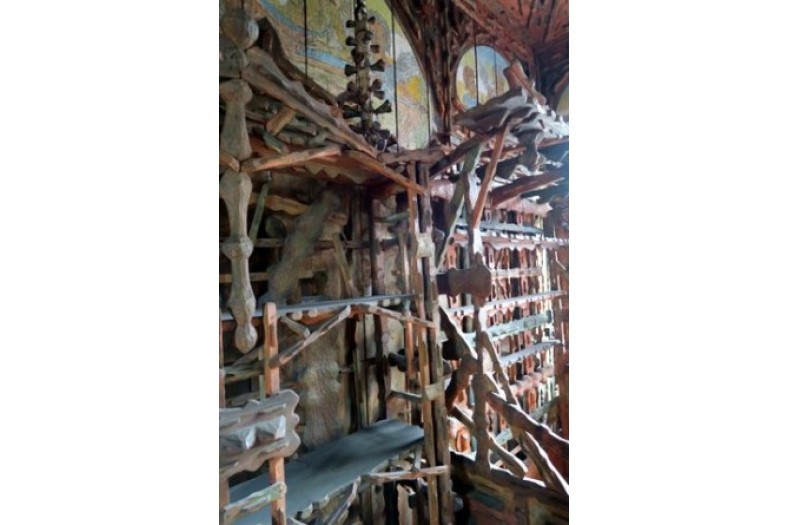

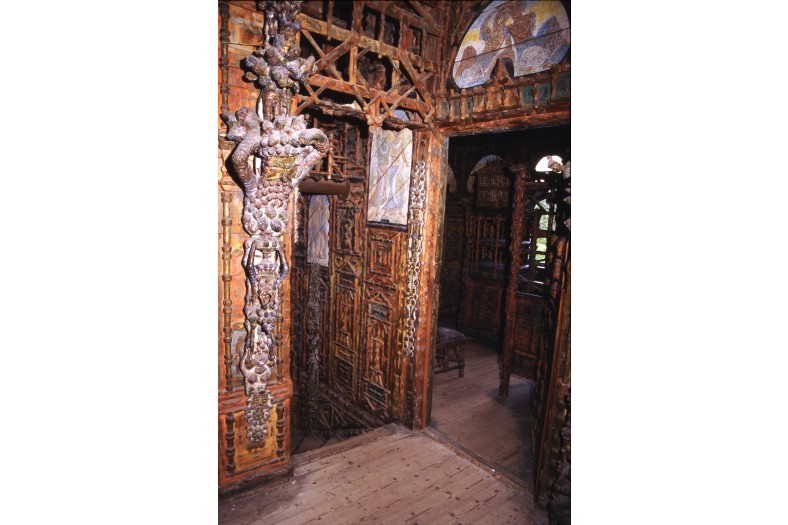

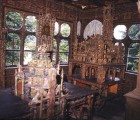

However, Junker's house is special, not only because of its decorative exterior, but even more so due to the decoration and furnishings of its interior. All of these objects were singlehandedly made by Junker.

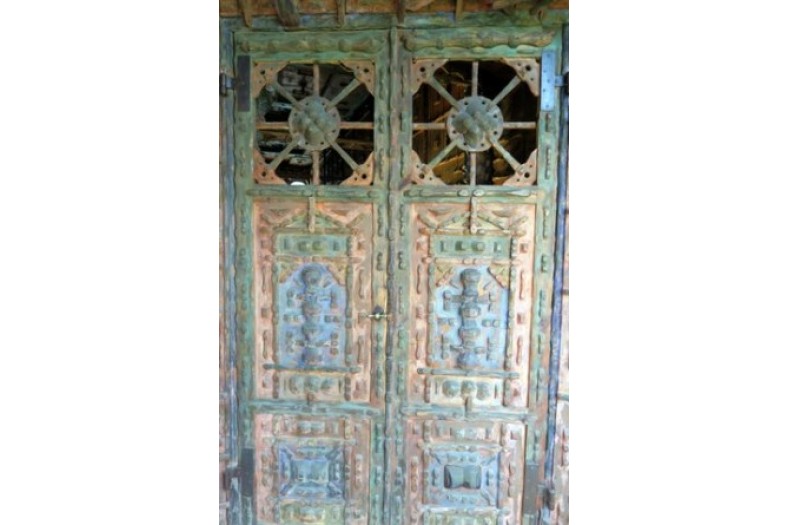

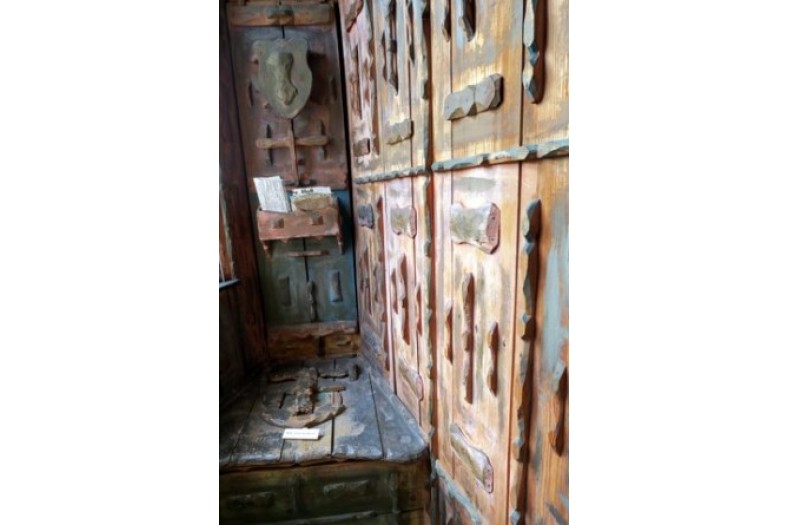

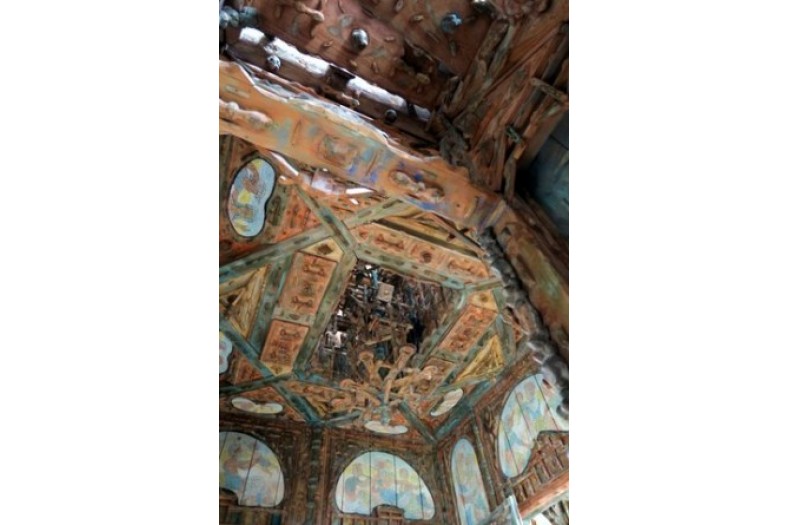

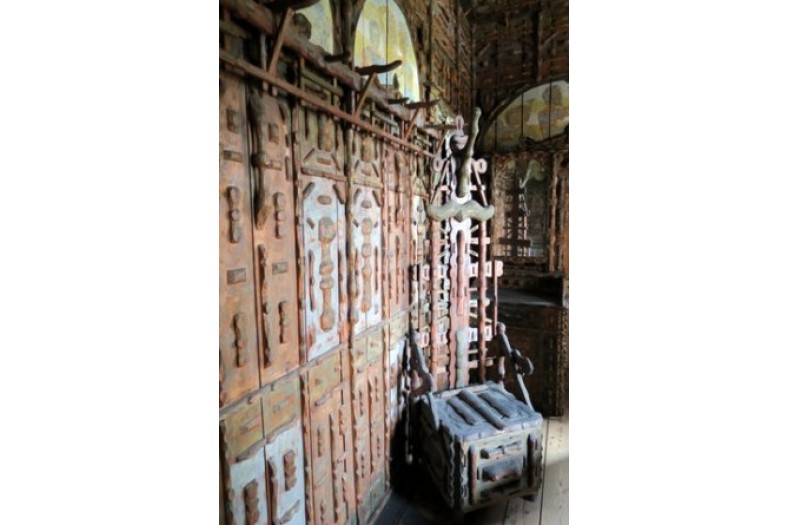

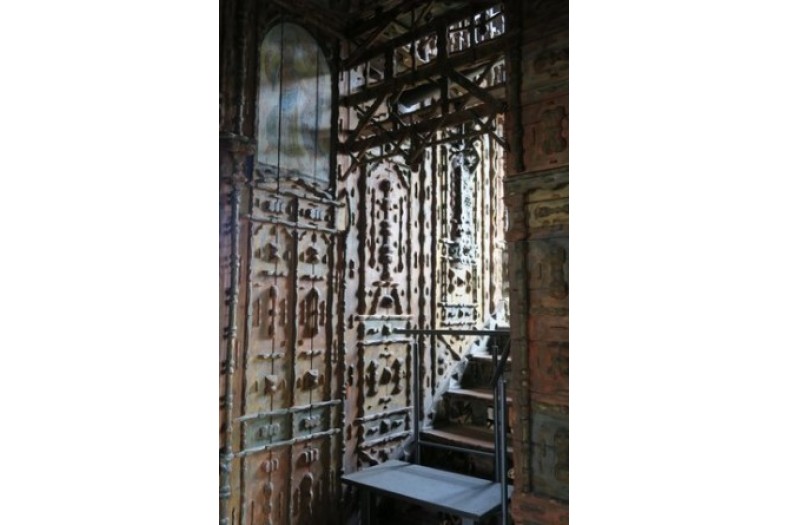

The walls of the house's rooms were lined with wooden panels, each of which were decorated, in turn, with carved or painted symmetrically-placed wooden applications. Most walls also display large oval medallion-shaped panels, many of which contain a painted representation of a person, and often relate to the function of the room.

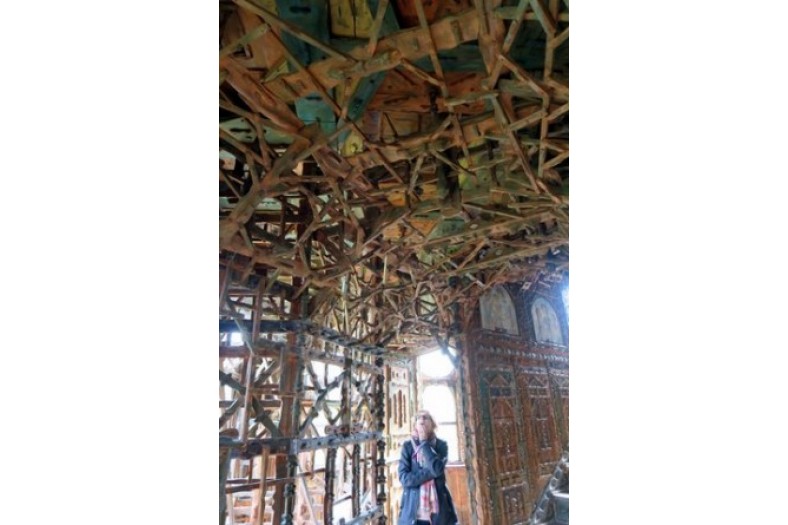

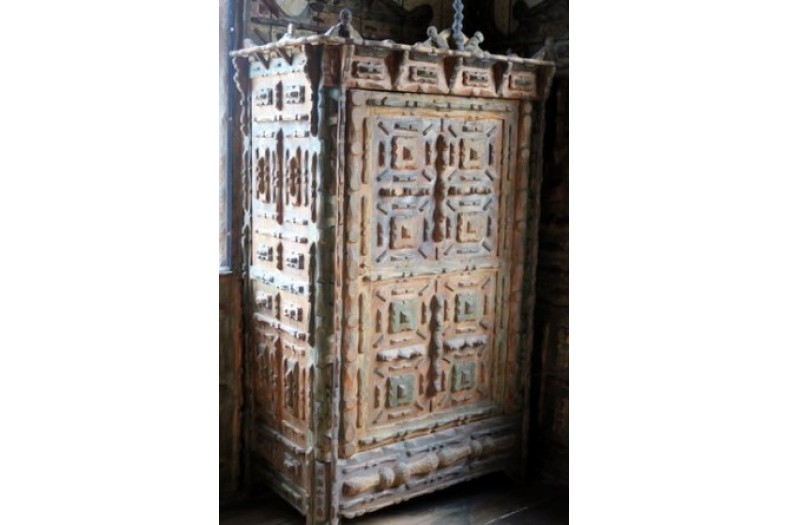

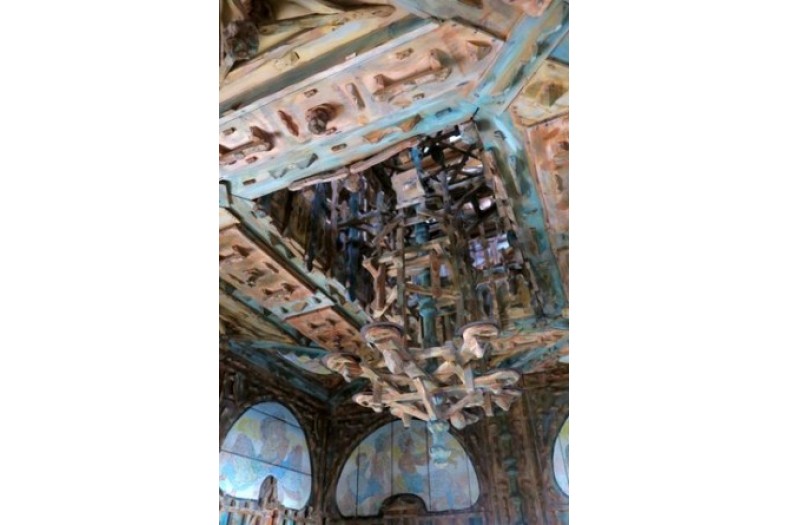

Junker also made all of the furniture, with all pieces painted in a very particular way, often by using an undercoat layer of silver-, gold-, or copper-colored powder, which in its turn was painted with a dark-colored layer of paint, a procedure that gave the interior a very special shine. Most of the furniture has also been adorned with carved wooden elements. Some pieces, such as a sofa and chairs, feature a high and exuberant wooden gridwork on the back. Other pieces, such as a writing desk and a wardrobe, were elaborately detailed with carved wooden decorations. It is noteworthy that the gridwork Junker used in decorating some of the furniture also appears in large-scale freestanding constructed or decorated elements, such as around the staircase to the cellar or as ceiling decoration.

Junker also constructed more than one hundred separate freestanding or wall-mounted wooden sculptures, with images of people, flowers, or combinations thereof. In addition, many of the walls as well as many pieces of furniture are decorated with painted scenes, often realistically showing figurative scenes like that of a family.

Junker's artwork cannot be linked directly to one of the existing art movements of his time. He turned away from the classical style he had learned at the Academy in Munich, and searched for his own way, combining architecture, sculpture, and painting to create what the Germans call a Gesamtkunstwerk [total or complete artwork]. As he did not work within the commonly-accepted categories, the art world of his time did not pay any attention to Karl Junker.

In 1928, sixteen years after Junker’s death on January 24, 1912 from pneumonia, German psychiatrist Gerhard Kreyenberg – who had never seen nor spoken to Junker – wrote an article in a professional magazine classifying Junker as a schizophrenic, a qualification that was subsequently adopted by many other authors (including, for example, American writer John MacGregor), who subsequently also incorporated Junker into the field of “outsider art.”

In the meantime, these classifications have been adjusted. In the 1980s interest in Junker's work increased and contemporary art historians such as Carolin Mischer no longer support the diagnosis of schizophrenia, reasoning that on the sole basis of viewing an artwork, and without meeting and diagnosing the artist, one cannot draw any conclusion about his/her psychic condition, as Hans Prinzhorn had already argued. And, with regard to “outsider art,” it is argued that the distinguishing criterion of being self-taught does not suit Junker, who had documented professional training as an artist.[i]

It is not surprising, however, that his fellow citizens may have considered Junker as somewhat eccentric. Never married, spending all his time constructing his artwork, he did not socialize, and he left his house just to do some shopping or have a meal at a nearby restaurant. However, he was not anti-social: when interested visitors presented themselves at the door to see his art, he took the time to inform them and give them a tour.

The house has withstood the ravages of time, and more than one hundred year later, its exterior and interior still appear as Junker intended, although certain components display some damage and the woodwork has become vulnerable over the passing of the seasons. Therefore, in 1962 the city of Lemgo bought the house, took protective measures, and developed plans for its future. Around 2000 a restoration was begun, which was finished in 2004.

Today Junker's house has become a museum, and visitors are welcomed in an annex building, which has a display of Junker's visual art and is linked to the original house with a glass corridor. However, to protect the fragile wooden structures, not all rooms within the building are open to the public.

- Henk van Es

- the Junkerhaus website: http://www.junkerhaus.de/

[i] The authors referred to in above two paragraphs are

- Gerhard Kreyenberg"Das Junkerhaus zu Lemgo. Ein Beitrag zur Bildnerei der Schizophrenen" in: Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie u. Psychiatrie no.114, Berlin, 1928, p.152-172).

- John MacGregor, "Junker House. The architecture of madness," in Raw Vision, 41 (2002): 48-57

- Carolin Mischer, Das Junkerhaus in Lemgo und der Künstler Karl Junker. Künstlerisches Manifest oder Ausserseiterkunst? Köln [SHVerslag], 2011)

- Hans Prinzhorn, Bildnerei des Geistekranken: ein Beitrag zur Psychologie und Psychopathologie der Gestaltung. Berlin, 1922

Map & Site Information

36 Hamelner Straße

Lemgo, Nordrhein-Westfalen, 32657

de

Latitude/Longitude: 52.02599 / 8.91755

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.