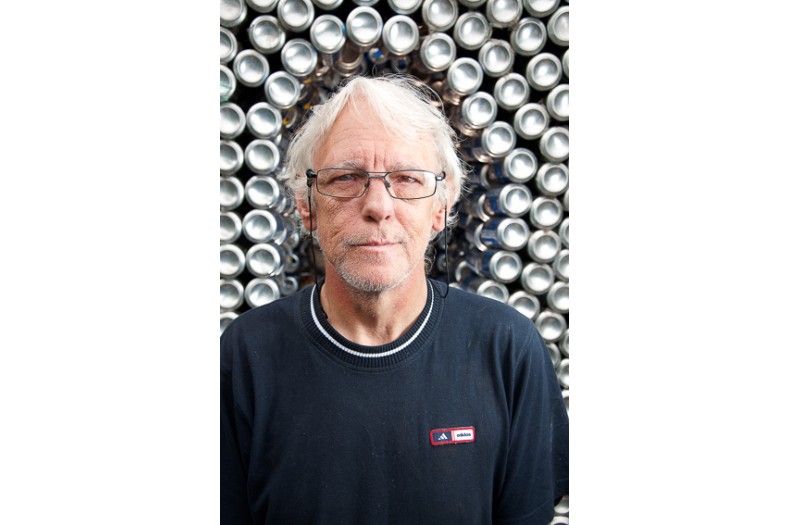

The Can HousePhilip Muspratt (1952 - 2015)

Non Extant

Raby Road, Hartlepool, TS24, United Kingdom

1995–2015

The Can House was demolished to make way for development in 2018.

About the Artist/Site

Creativity knows no bounds, and people will use a seemingly endless variety of materials or possibilities to express, create or decorate. We use whatever is at hand, whether paint, paper, wood, metal, stone, glass; we’ve even used berry-juices and charred sticks – the former spat over splayed hands placed as stencils on cave walls, the latter to further mark those caves with living figures.

The buff brown and colored dirt of the very earth itself is used in the intricate sand “paintings” of the Navajo Indians. These sand paintings’ primary function, however, was for healing, not decoration.

Philip Muspratt, far removed in time from either the Navajo or prehistoric cave dwellers, has also used the most basic of materials he had at hand to create, decorate, and, in a way, to bring healing. His dirt-of-the-earth, common-as-muck material was the empty beer can: Carlsberg, Heineken, Fosters, whatever – drank dry and discarded. Trash to most, except for Muspratt, ex-soldier and retired bus driver who, from 1995 until his death, decorated his modest, semi-detached house and garden in Hartlepool with beer bottles and then, from about 2005, with beer cans.

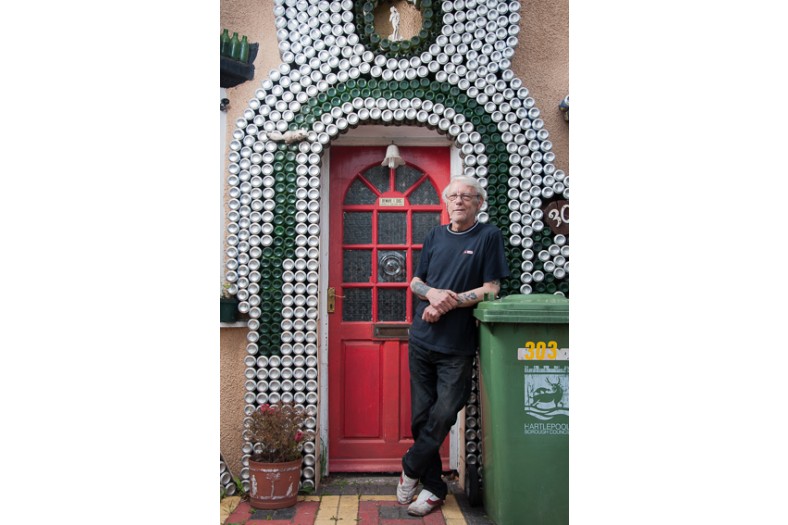

The house, not surprisingly, is fondly known as The Can House, and Muspratt himself as “The Can Man” or “Beernardo da Vinci,” as he was dubbed by the local newspaper. Muspratt’s work is a gem of creativity in an otherwise unspectacular northeastern coastal town that has seen better days.

Muspratt, whose only recollection of ever doing any art was when he was a school child, has created a unique work that consists of about 75,000 empty cans held mainly in place with waterproof, industrial-grade adhesive.

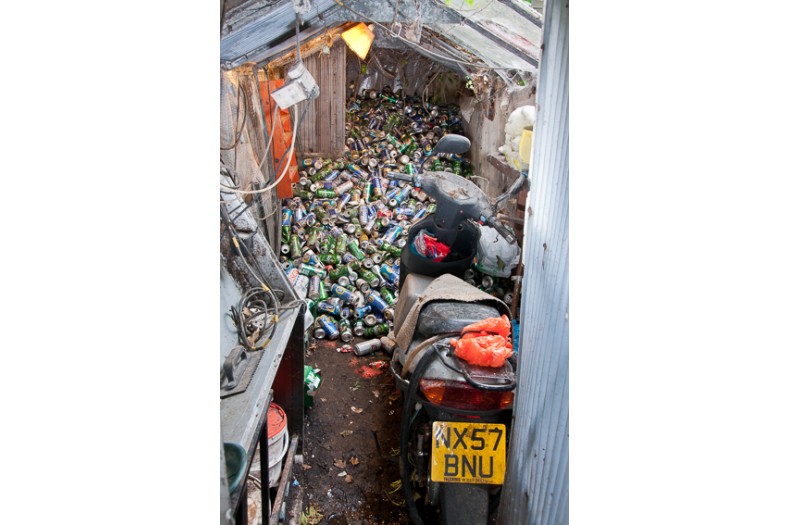

It all started when my dad, who was 92 at the time, moved in with me and my wife after my mum died. He was a deaf mute, always had been, and I wanted to do something to cheer him up. I simply started putting colorful odds and sods, jokey stuff, in the back garden to make him smile. I never had and still don’t have any real plan. Then one day, when I was at my son’s place, I saw the piles of empty beer bottles him and his mates had emptied and figured I’d do a wall of bottles. Because my son’s an alcoholic, I had an almost endless supply of bottles and ended up with a wall in the back garden two bottles thick, five feet high, and 23 feet long. That took about five months. When he stopped drinking bottled beer he moved onto cans and, for some reason, I started collecting them.

After a while, Muspratt had a shed full of empty cans. Someone told him he could get a penny for each as scrap metal, so he decided on two things: to continue decorating his garden and house with the empties, and to collect cans to raise money to clean up a local war memorial that had fallen into disrepair.

As the work continued and news of it spread, Muspratt found himself on the receiving end of supporters and well-wishers bringing him sacks of their empties. “I figured I could get a million cans,” he said. Public opinion was, unsurprisingly, divided as to what was slowly taking shape. To some it was “a bloody eyesore” and to others “bloody brilliant.” Muspratt said, “When the sun shines on all the metal it looks really good, and I just want to do more and more.”

This part of the country does not usually feature in any tourist guides. However, the house does make a blip on the radar of some who leave the beaten path to see the Can House for themselves. Once there, they will take a few pictures, drink a beer or two in the street, and leave their empties as a token offering.

Due to the general demolition in the area (Muspratt’s house was due to be demolished in 2013, but it is still standing), most of the pubs are derelict and boarded up, so quite a number of folks have instinctively gravitated to the Can House to drink. Muspratt’s place became a true public house with his living room hardly ever empty.

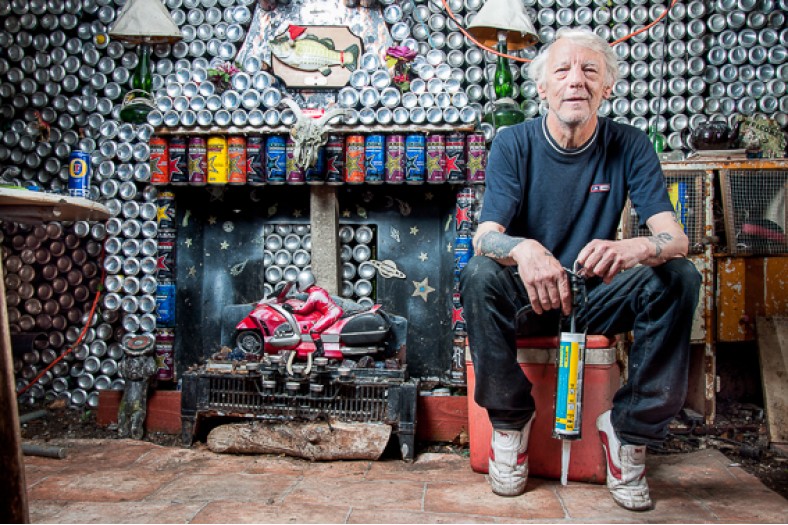

Initially, Muspratt’s small back garden is slightly disorienting, due to the constant undulation of countless cans. There is a many-tiered ornamental fountain, lit at night by Christmas lights and decorated with numerous plastic action heroes and cartoon characters, leaping dolphins, a smattering of kitsch “welcome to my garden” ceramic plates around the base, and topped off with a large, bespectacled, skateboarding Smurf. Nearby, a hanging (not hung!) furry monkey with a huge pink plastic boxing glove swings from a bright orange rope

To his original green bottled wall Muspratt has added a layer of cans, constructed to form a variety of alcoves complete with bathroom glass shelves. On these shelves are, among other objects, a many-sailed sailing ship fashioned from a bull’s horn, and a typical tourist’s souvenir wine bottle covered with shells next to a two-can-tall Blackpool tower surrounded by luminous stars and planets. One shelf is stuffed with plastic African animals, and on another a prancing glass horse is flanked and protected by two toy dogs as well as by Bill and Ben, the Flower Pot Men of the 1950s English children’s television series. Directly opposite this wall of wonders, crowned with a large star to rival any piece of Soviet architecture, is a larger alcove that hosts an oversized metal football (festooned with chains of plastic sausages) that is actually a well-used barbecue.

Surprisingly, considering the simplicity of the materials, most of the construction has stayed in place. One notable exception is a large cross made from green bottles. It was not properly fixed to the gable wall and fell one Easter Sunday. Not one to give up, Muspratt started again, learning from his mistakes and simply carrying on.

As the property is privately owned, access to the garden is not guaranteed, but a polite request to see it will not be amiss. If no one is home, the house is visible from the street.

With no preservation order on the house or the artwork, it is anticipated that it will soon be demolished.

~Peter Wilson*

*This text was adapted from Wilson’s article “Beernado da Vinci,” Raw Vision 91 (Fall 2016): 44 – 47.

Update: The Can House was demolished to make way for new development in 2018. Learn more here.

Materials

beer cans and bottles

MEDIA

Can House

Can House documentary by Maxy Neil Bianco of Daft as Rags. Trigger warning: depictions of addiction and alcohol abuse. In a broken old port town stranded deep up north, a strange, magical,shrine-like building has appeared. in a neighborhood falling into such profound decline that the street lights have been switched off and many houses have been boarded up waiting for new development that may never come,one particular pebble dashed council house has mysteriously blossomed into new life, covered with ever more intricate and beautiful patterns, patterns made out of Fosters beer cans, like some alcoholic gingerbread house at the end of the world...

Map & Site Information

Raby Road, TS24

gb

Latitude/Longitude: 54.6929021 / -1.2192068

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

Martin Wallace June 9, 2021

Can House was demolished 2018. See this article: https://www.vice.com/en/article/wjmj7b/rip-the-can-house-a-cultural-landmark-made-from-empty-beer-cans 51 minute film about the place here: https://vimeo.com/112523967 Keep up the good work, Martin