It was boiling hot in Simi Valley on the day I first visited Bottle Village. I was not yet twelve years old and wore cotton, shortie pajamas, the only clothes that didn’t scrape like sandpaper against the sunburn I’d acquired the day before at Will Rogers State Beach. For close to ten days, we’d been travelling the back roads from Albuquerque, New Mexico to the Golden State with dad at the wheel of a brown Chevy pick-up he’d dubbed “Daedalus.” My grandmother, Rose, rode shotgun, and, in the back, under the camper shell, me, my brother, and our three best friends from school nestled in sleeping bags, loose as popcorn. We’d been to Disneyland and Knott’s Berry Farm, but Dad was never content with only the main tourist spots. He ballpoint tattooed the pages of his Rand McNally road atlas with alternate routes, and drew stars to mark roadside attractions, artists’ homes, and miscellaneous wonders.

Though she was over eighty years old, Tressa “Grandma” Prisbrey was only too happy to give us the special tour of the sixteen buildings she’d constructed using glass bottles and concrete. She poured cold lemonade into paper cups and held up the smallest and largest pencils in her vast collection. That big pencil, long as my arm, was kept in a corner guarded by the most enormous black widow spider I’d ever seen. Though the spider gave me the chills, my friends and I were distracted by the way sunlight streamed through colored glass and traced cool green designs on our crimson skin. Outside we made a game of finding familiar objects in the tile and concrete pathways – forks and spoons, a porcelain dog, a doll, a flower, a gun. My brother crouched and traced his fingers over the shape of the weapon.

“Can’t hurt anyone there,” Grandma Prisbrey said. She laughed and nudged us forward, pointing out a row of glass television tubes, and a collection of large metal coils nestled in a raised bed. “My spring garden,” she said, laying the emphasis on the word spring.

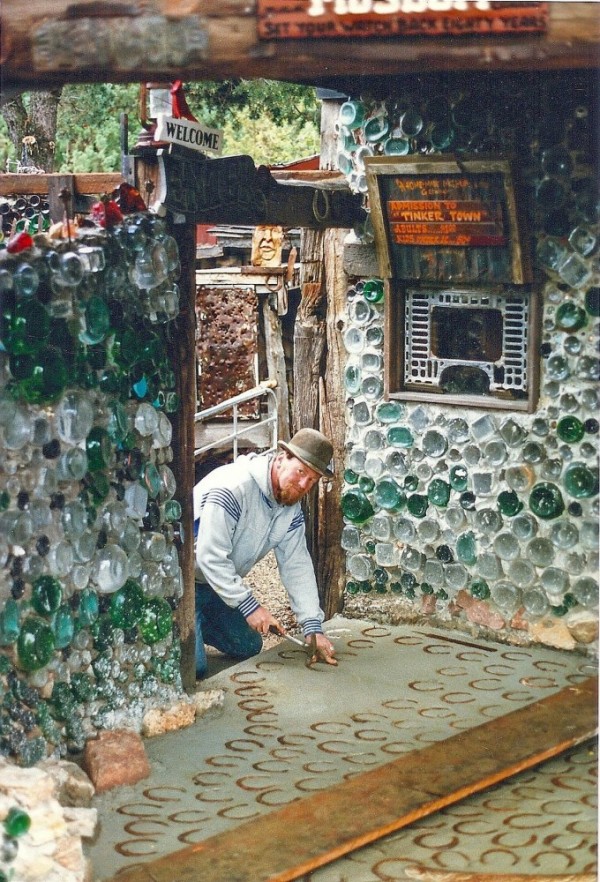

I don’t know if dad was taking actual notes, but he was definitely alert to possibility. At this point, he’d already begun to build the series of small interconnected bottle walls that would eventually surround our house in Sandia Park and become the facade of Tinkertown Museum.

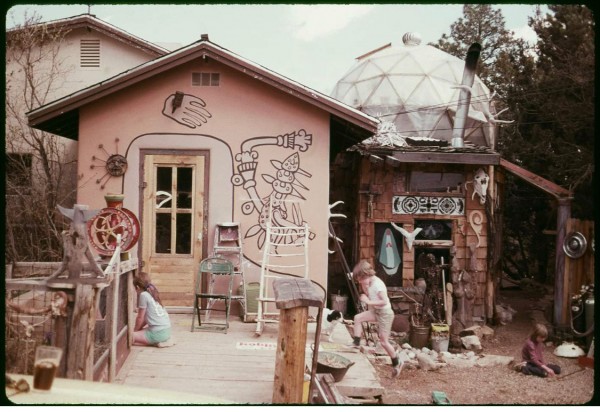

The Ward home in the mid-1970s before it became the Tinkertown Museum. Photo courtesy of the Ward family.

Dad often compared ideas to flowers – they were everywhere, ripe for the picking. “Check this,” he’d say, as he pulled the parking brake on the truck, hopped out, and took long strides across a dusty driveway or winding gravel path. He’d gently run his fingers over weathered gray siding, rusted tin, or seashell mosaics. With his hands moving like birds in the air, he’d direct my gaze up, up, to a jagged roofline or welded spire. And he was chatty and ready with a joke, able to nudge even the most reserved of hosts into a little back and forth.

My sunburn had faded enough so that I was back in regular clothes by the time we hit Possum Trot. Though creator Calvin Black was long gone, his Mojave desert creation was hanging on thanks to the efforts of his wife, Ruby, who kept nightly vigils with a rifle across her knees. In the near constant wind, the high-pitched recorded voices of the Bird Cage Theatre performers mingled with sand in the air. The carved figures wore tattered and sun-bleached clothing that flapped against their stiff arms and legs. Their wide, painted eyes seemed to stare straight into mine.

Is it mad to imagine they saw into the future? What might those figures make of their new homes in temperature controlled museums across the country? Did they know that one day the desert wind would blow unimpeded across the land where Possum Trot once stood? Could they make any sense out of the fact that one day my dad, too, would be gone?

“You’re a living artifact,” SPACES founder Seymour Rosen told me just a year or so after my father’s death. In search of guidance (or maybe just some good company,) I’d gone to visit him in his cluttered offices in Los Angeles. We sat together and swapped stories. He recounted the early days when he’d worked to save Watts Towers and advocated for the California Landmark designation of numerous sites, including Possum Trot and Bottle Village. He might have said something about the hazards of angry neighbors and warned against the building inspectors. He might’ve recommended an excursion up to Cambria to collect moonstones and visit Nitt Witt Ridge. Or maybe I’m confusing him with my dad. Rosen and Dad seemed to be twin spirits – enthusiastic, warmhearted, sometimes a little cranky. They shared an ability to see possibility in the broken and the cast-off. I wish I’d taken better notes.

As a kid, I pulled up a barstool next to Dad and drank sarsaparilla at the Long Horn Ranch Bar. I measured finishing nails on a metal scale at our local hardware store. Together we hauled rocks from the side of the road to add to his walls, and combed the aisles of bookstores, antique shops and flea markets. He taught me how to sew sleeves on a doll-sized shirt and told me the secret, whether drawing a picture or writing a story, was to put my pen on the page and just keep my hand moving. Whenever he asked “got a minute?” I said “yes” even though I didn’t know if I’d be hefting railroad ties or taking a ride to the Dairy Queen for a pineapple shake. Dad trained me to look at a discarded plastic creamer container and see an elephant tub or the hat for a clown. He reminded me that it doesn’t take fancy tools or materials to make art. He carved all the figures in Tinkertown out of what he deemed “parking lot pine,” and turned every diner placemat into a canvas. If he saw a spark of talent or a faint glimmer of interest, he was only too happy to give away his paint, his brushes, his pencils and pens. “It’s all we can do,” he told me once, “just help each other out now and then.”

When I returned to Bottle Village in my late forties, I came with sunscreen in my pocket and a broom in my hand. I’d seen a call for volunteers and, thanks to Dad, I knew a thing or two about clearing pine needles out of bottle walls. Though the site had sustained massive damage in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, Grandma’s spirit was stronger than any temblor. She was with me. And so was Dad. I half expected to catch a glimpse of myself – that kid with the long, tangled pony tail and a mouthful of braces – dropping a penny into the wishing well.

When I was little, I often wished that my dad would live forever. Now that I’m all grown up, I realize that, in a way, he has.

Ross Ward at work creating the concrete Tinkertown Museum entrance walkway in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Tinkertown Museum.

Tanya Ward Goodman is the author of the memoir, Leaving Tinkertown (University of New Mexico Press.) Her writing has appeared in numerous publications, including The Washington Post, Variable West, Luxe Magazine, and The Orange County Register and the Museum of Art and History catalog for Susan Feldman MOC (My Own City.) She is Director of Special Projects at Tinkertown Museum and volunteers at Bottle Village and numerous other community organizations.

Feature photo: The author photographed as a child at Miles Mahan's Hula Ville in Victorville, CA. Photo: Ross Ward, 1980

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.