Photographer, cultural advocate, and SPACES founder Seymour Rosen is well-known within the world of art environments for his dogged determination to protect place- and life-specific works of art and expand their recognition as culturally and creatively significant sites. Rosen first visited the Watts Towers in 1952 – the very beginning of his photography career – and his subsequent dedication to art environments continued throughout his life. However, Rosen’s appreciation of cultural production was expansive and included many more forms of human expression – from art cars and existential messages left under overpasses to storefront churches and intricately woven baked goods.

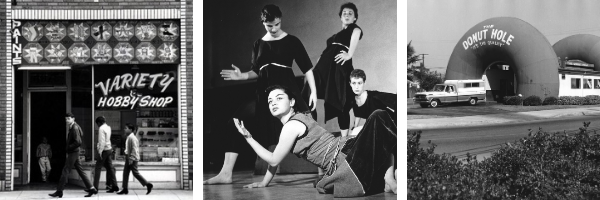

Photos by Seymour Rosen

In addition to his exploration of the vernacular, Rosen traversed the world of institutional art making during his time as a photographer with the Ferus Gallery – a contemporary art gallery frequently credited as one of the birthplaces of modern art in mid-century Los Angeles. During his time at Ferus, Rosen befriended curators, gallerists, and artists like John Altoon and Ed Kienholz. (Kienholz and Rosen remained friends, and the assemblage artist and his wife and collaborator Nancy served on the SPACES Board of Advisors for a time.)

Ferus Gallery and a Warhol exhibition featuring the recognizable Campbell's soup cans.

When Rosen sought reassignment as a photographer during his military service in the late 1950s, both Kienholz and Altoon provided recommendations. “I have had the pleasure of seeing his work over the last two years and I find his pictures talented in expression, and altogether refreshing, particularly his color slides of Watts, which caused quite a sensation in Los Angeles at circles this year,” wrote Altoon. Kienholz spoke of Rosen as a collaborator who was “intelligent and inspirational.”

Watts Towers, Seymour Rosen

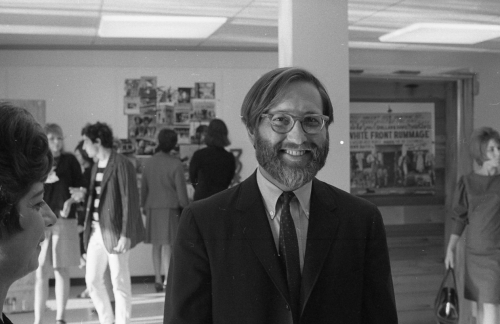

While Rosen continually saw himself working on the outside of the sphere of institutional recognition, the artist community of Los Angeles championed his work and oftentimes found inspiration in the materials and spirit of the creative expressions presented in his photos. One of Rosen’s significant contributions to L.A.’s mid-century cultural milieu was born out of a challenge to acquire institutional support. Rosen recognized that many of the places and practices he was dedicated to sharing were in danger of disappearing, and as such, in great need of documentation. When the Guggenheim Foundation rejected his application to perform the task of recording these artistic activities for posterity, Rosen hypothesized this was due to his lack of “academic credentials.” To boost his credibility, Henry Hopkins, curator and educator at LACMA and friend of Rosen’s, offered him an exhibition at the museum in 1966.

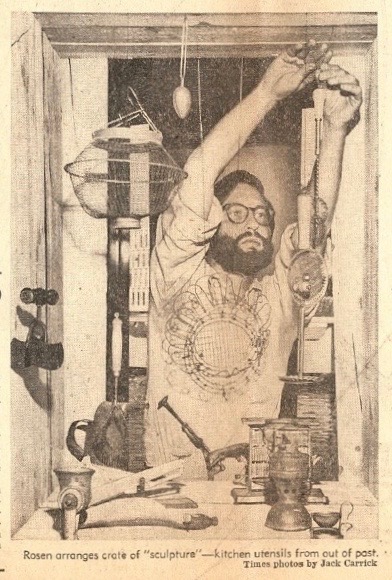

Seymour installing I Am Alive in 1966 at LACMA

The catalogue of the resulting exhibition I Am Alive opens with a portion of a poem written by Don Marquis’ cockroach character Archy featured in his Evening Sun column:

Poets are always asking

Where do the little roses go

Underneath the snow

But no one ever thinks to say

Where do the little insects stay

This is because as a general rule

Roses are more

Handsome than insects

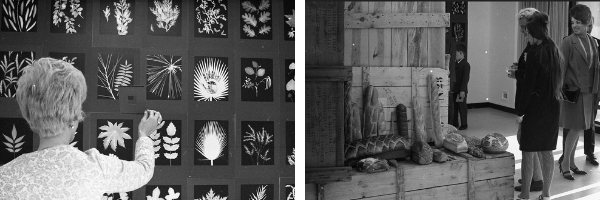

Archy’s poem sets up Rosen’s curatorial agenda to challenge what he perceived to be the established value system for the ordinary, the handmade, the collected, the junked, the everyday expressions of folks in the community surrounding the museum. Photos and objects collected to exhibit – all from within a ten mile radius of the museum and only that far as to include the Watts Towers – were displayed inside and around wooden shipping crates that visitors were encouraged to open and investigate. Rosen wrote in the catalogue that the exhibition included “various methods by which man says “I exist… I am alive.”

Visitors at the I Am Alive exhibition opening. Seymour Rosen, 1966.

The exhibition was installed in the Junior Arts Workshop, where Rosen relished the opportunity to be in dialogue with the museum’s youngest constituents, saying “this exhibition represents an effort to present stimulating materials that may graphically ‘turn on’ the students to the magic, excitement, and joy in the discovery of the world around him.”

Visitors at the I Am Alive exhibition opening. Seymour Rosen, 1966.

The environment of joy that Rosen cultivated was obvious not only to the children visitors but also local arts writers. Gordon Hazlitt began his review by identifying the contemporary art world as “a very snobbish place.” He went on,

“I am Alive is not an art show, I suspect, but is a Medeival [sic] morality play made modern and presented on behalf of art. It is an Everyman show in which each of us is invited to be his own artist and learn to use his eyes afresh and see the world again as if for the first time… I suggest that it occupy permanently a corner of the third floor of the Ahmanson Gallery. Then when outrage comes, automatically a recorded voice says, “Please step this way.” The person is required to see “I am Alive.” Laughter and discovery would melt the outrage and even would entice the Philistine into the very attitude which is the basis of all modern art – that of seeing the abstract form that underlies the world around us. Outrage passes on, Magician Rosen waves his hand and Everyman Artist trips out.”

Visitors at the I Am Alive exhibition opening. Seymour Rosen, 1966.

Long after the exhibition, Hopkins continued to recognize the cultural impact of Rosen’s work and champion his important role in the avant-garde arts movement in southern California, including writing in the introduction of the catalogue for the 1989 exhibition Forty Years of California Assemblage, “Our association with the Towers also led us to the photographer Seymour Rosen, who had become so absorbed by the Towers that he had begun a life work of documenting hundreds of naive, folk, and ethnic ceremonial environments in California and throughout the United States.” While Rosen saw the Guggenheim rejection as indicative of his status as an outsider to institutionally accepted art making at the time, the work of Simon Rodia and other environment builders that Rosen obsessively documented became, “important source material for the emerging assemblage artists,” according to Hopkins

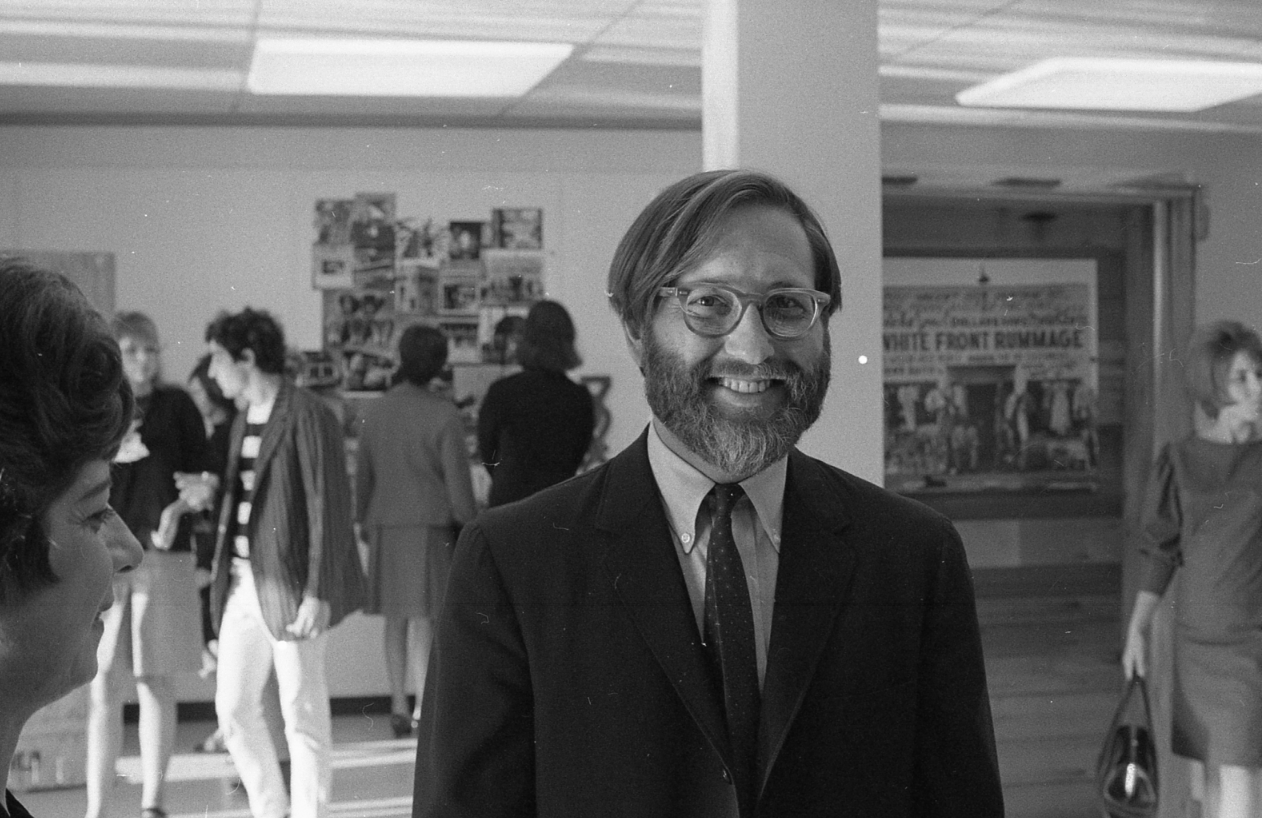

Rosen at the opening of I Am Alive

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.