The Gregangelo Museum is a space dedicated to connection through storytelling, the personal home of Gregangelo Hererra, and a headquarters of his dance troupe and entertainment company. Tucked in a historic home in the Balboa Terrace neighborhood of San Francisco, this museum has been a community center for LGBTQ+ and emerging artists of the area since the 1980s. In 2024, it was designated as San Francisco's 318th Landmark.

Could you introduce yourselves?

GH: I'm Gregangelo. I'm a local, born and raised San Francisco artist, and I did not set out to become a landmark or do any of it. I'm pretty much primarily in the entertainment business. There was a lot of combination of visual art, theatrical art, and entertainment. We turned the place inside out. It became incredibly controversial because we were just doing our job as artists, because we could. That eventually led to Heather.

I got a call one day from a supervisor saying, “there's people trying to shut you down. That's not going to happen. There's a lot of steps we're going to be taking. I'm going to, because of what you contributed to the arts and culture of the city, be applying for landmark status. It’s going to be a pain in the ass. You're not going to like it. It's going to take a few years. It's going to be expensive.” And she hung up on me. And that's how I came across Heather.

HS: Hi, my name is Heather Samuels. I am a planner with the SF Planning Department, and I've been with the Department for a little over three years now.

How would you describe the space?

GH: Heather, you can probably describe the place better than I can. I'm too in it. So if you can…

HS: That’s fair. It's this amazing conglomerate of dozens, if not more, artists' work. Every inch is covered in a different material and different style. It takes you through nuanced stories of what San Francisco is from a native's perspective. Also, we touched on your personal story, Greg, of just how it was built originally out of grief, and it became way more and became a more public spectacle, and then became more of a community space than anything in the end.

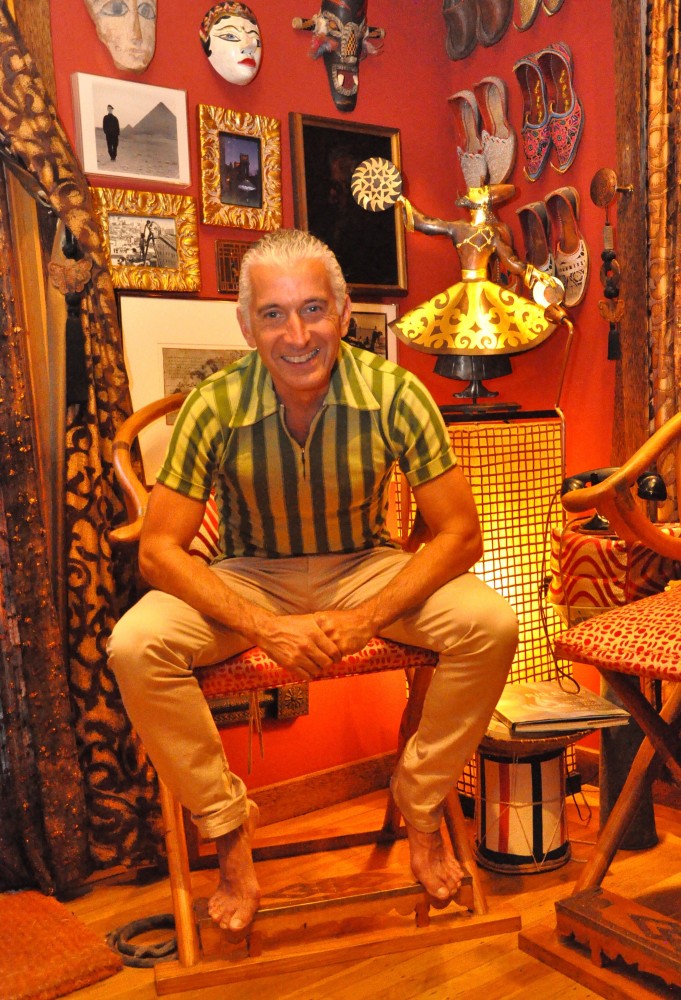

Photo of Gregangelo Museum. Photo courtesy of Zoart Photography

Could you describe the process of historic designation for the Gregangelo Museum?

HS: I can take you through the very clinical, city procedural situation that happened. So Gregangelo was nominated for a legacy business registry, which is a program that I run here for the city, but back then I was just a normal planner working on them. If a business has been open for 30 plus years and contributes to the city, we load them up with support – financial and other types of support from the city – from the Office of Small Business.

And when I was reviewing the application, I was like, oh, this is not a legal use. We have to make them [Museum] a legal use in order to do that. Through that, we were like, okay, so this is a residential house district and we can't really have commercial or event spaces. What can we do?

The planning code allows for landmarks and other historic buildings to have a different type of use, so we can continue the preservation and that use in the space, rather than abandoning it and just making it vacant because it's not a house anymore. Through the help of Supervisor Melgar and Gregangelo’s whole team, we pursued the landmark designation so that we could then change the use.

And now both of those things are done. And we got the legacy business designation done, because we finally changed the use, now we're doing the physical changes that it needs to be building code compliant or ADA compliant.

Does the historic designation affect the use of your space as a personal home or a public museum? How do you balance those two, did any changes have to be made?

GH: So there is no balance, actually. There's no balance. And I think that's true of any artist. You're just living it. I often joke because I ran a circus company for about 25 years and all the spiritualists were like, “we're just trying to find our balance”. That's funny. When we find our balance, we get a standing ovation, and then we fall. It lasts for two seconds.

So maybe you shouldn't try to find your balance, just keep going. Just keep moving. I don't know. So It's wholeheartedly 100%, just living it, walking it, being as earnest as possible because you don't want to create it. It's interesting because in the entertainment business, we'd create acts and personas and characters for ourselves. And now I just decided I can't. I just have to be myself because this is ridiculous. I'm not going to start acting. Otherwise, I would never be anything.

And that's exactly the value that we do for every guest who comes through. We didn't realize we were doing it, and I don't think the guests realized it was happening. The experiences are so earnest and so reflective and thoughtful and funny and there’s laughter through tears. And there's marriages and divorces and breakups and makeups and friendships being made. It's so genuine and earnest that that's just how I think all of the artists here have just learned, just keep it real. But with kindness. Just uplifting as you can.

Tour group led by a docent. Photo courtesy of Hiromi Yoshida

At what point did the work in the home become collaborative? When did you start either inviting people to work inside the house or did people just start asking you?

GH: I did a lot of it myself in the early years. But very soon after, I'd say by the late '80s, early '90s, artists were just coming because I was making a living at that time as an artist. Again, I didn't even know how or why, I was just doing it. I'm a hyper guy. I started attracting a lot of artists asking me, “how are you making a living?” I don't know, but I need help.

I'm like, I need help. I would start doing these collaborative things; the costumes, the films for the shows, the writing, the music, the choreography. It was mostly in performing arts at that time, but at the same time, we were always labbing the house. I mean, for example, one day my brother was here, and he walked in a room and fell right through the floor because the floor was that rotted out. I was like, oh, shit. It's all these weird circumstances that led to, I need to repair this. Then, well, I'm working on this story.

Sometimes I would storyboard. The house is really a storyboard for a lot of the shows that we've done. The paintings in the house are literal storyboards for shows that are done in a style that's interesting enough to hang them as paintings.

How would you describe the relationship with the city right now? There are articles that like to highlight the tension with neighbors and local government. How is that going since the designation was made?

GH: Well, with my immediate neighbors, it's always been wonderful. I've never, ever, ever had a problem with them. During the whole process, people were like, “How can the city do-?” I'm like, No, the city is helping me. You don't get it. “Well, how can your neighbors do-?,” I'm like, It's not my neighbors. It's three petty old fogies who just needed something to lash out at, rather than something to build.

While they were lashing out, I mean, just the nature of my personality, I'm like, well come help. You're giving me a misunderstanding. I would invite them, come help. These are people within the HOA district.

And Heather has been so great in articulating who we are and what we do when they show up in the courtrooms, and do all the due process.

Detail of Gregangelo Museum. Photo courtesy of Zoart Photography

I have a question for Heather. The historic preservation field is traditionally pretty stringent in terms of how it assigns historic value to places. I'm curious about how this collaboration with Gregangelo went over, considering that it's still an active space with an active artist who's living there and changing things all the time. How did that work with the landmark status? Is this a new thing for your office, or have you guys been doing work like this previously?

HS: I would say, in terms of the specific criteria, we really focused on him being a historic person at this time, and then also the space itself being an art form and a physical architectural feat. In the landmarking process, when it's proposed to us as a landmark by the supervisor, we mostly push it through and develop the question, why is it important?

Why is the supervisor or the community pointing out that this is a place that needs to be preserved and a statement of San Francisco? Then take it through our personal criteria of is it an important person, story, event, so on, so forth. Then is it intangible? Is it tangible? Then propose it to the different boards. We have the Historic Preservation Commission, and they recommend it to the Board of Supervisors, which oversee each of the districts of San Francisco.

It passed through flying colors through all of them. I guess this one is more tangible than intangible. But I feel like lately we've been talking more about intangibles and cultural centers as places to be landmarked or preserved or districted.

The process of turning Gregangelo’s Museum into a historical landmark isn’t just about preserving a building—it’s about honoring a truly unique slice of San Francisco’s creative soul. Their collaboration shows how city planning and artistic vision can come together to protect spaces that spark imagination and community. Thank you to Gregangelo and Heather for sharing their perspective and experience with the SPACES Archives.

This interview was conducted by Annalise Flynn and Leah Zuberer via Zoom, July 2025.

Header image: Portrait of Gregangelo Herrera. Photo courtesy of Russel Johnson

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.