Cívica Don Aurelio Pérez López

Extant

Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, 19005, Spain

Located at CM-2011 between Brihuega and Masegoso de Tajuña (Guadalajara), Spain

About the Artist/Site

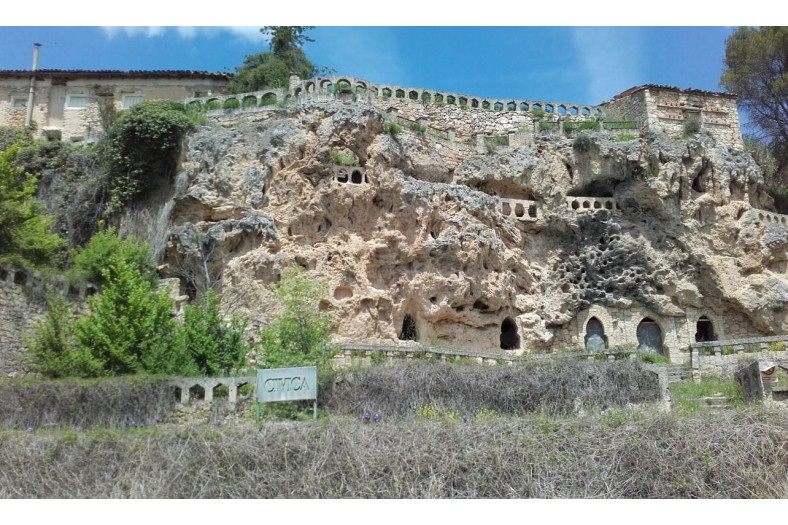

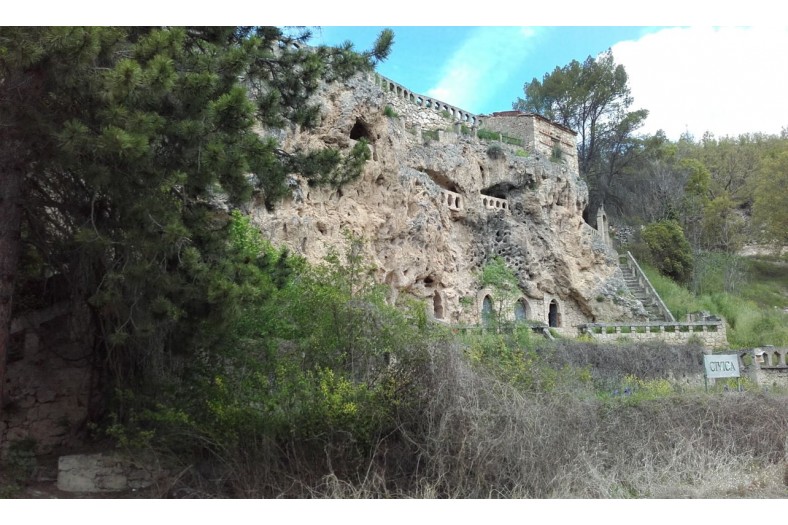

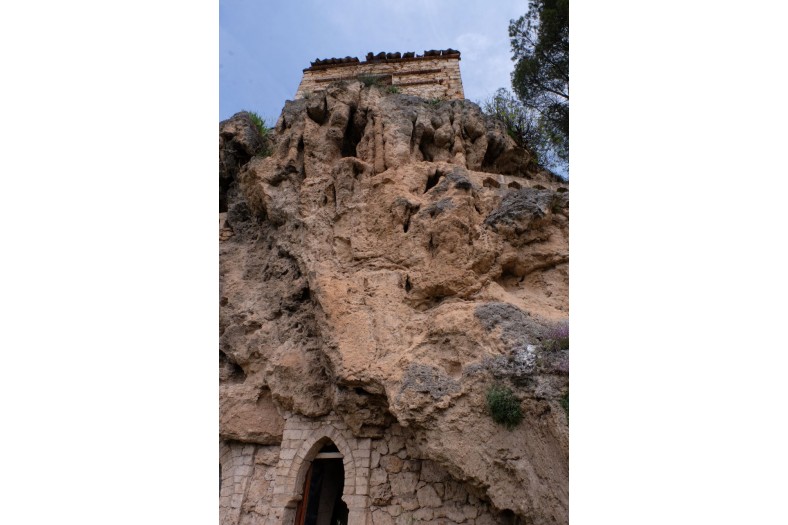

The Spanish landscape is dotted with thousands of manmade mementos of earlier times: stone castles, fortresses, bridges, and churches. Many have been abandoned but most still remain impressive, not only as reminders of historical narratives but as contemporary landmarks that dominate plains, riverbanks, and hillsides. There are so many stone constructions that the passerby naturally assumes that each has a bygone connection to a distant kingdom, nobility, or domain. So it is not surprising that some commentators have suggested that the structures of Cívica were developed by the monks of the Benedictine monastery at Villaviciosa de Tajuña during the Middle Ages or that perhaps it is all that is left of the ruins of a “pagan temple” from the Iberian epoch. Others have speculated that its winding dugout passageways once held the treasures of the Knights Templar, buried in haste during their retreat from Torija toward Medinaceli after the order was abolished between 1312 and 1320.

Yet in the case of Civica, these assumptions do not cleanly apply. Strangely, although historians have traced the general history of the hamlet itself from at least the 15th century, and have speculated about its possible use as a jail during the years of the Inquisition or as a secret location for torturing captured prisoners during the Civil War, little concrete information is known about the extant constructions themselves. While they manifest clear visual links not only to historical days but to distinct architectural styles, the site was, in fact, largely created during the 1950s and 1960s, with some construction possibly continuing up to the early ‘70s.

What is known is that Don Aurelio Pérez López, a priest from the tiny village of Valderrebollo, inherited this property and set to work changing the rocky hillside into a labyrinthine and multileveled complex. It is said that every day, rain or shine, he would leave Valderrebollo on foot, only some eight kilometers east, and after giving Mass in the village of Yela, would proceed almost six kilometers further toward Cívica, always refusing rides if they were offered. With a team of volunteers from Valderrebollo and Cogollar, he worked daily to excavate and erect a mysterious site that may never have been really inhabited. Historian Estrella Martín Acirón has conjectured that Pérez was inspired by the imagined or actual history of the site, and has spoken to locals who recounted that he kept a notebook in which he wrote about his discoveries, but the priest didn’t share this with anyone nor was it discovered subsequent to his passing.

In addition to the coved rooms and passageways, for some time a bar was installed at street level toward the west of the site. Boasting a rooftop terrace, no electricity was needed because drinks were cooled by the fresh waters of a waterfall emanating from a nearby spring and caught by stone tubs within; further, a cave in the rear provided the perfect temperature for storing wine. It functioned until the early years of the 1980s, and when Pérez was around and the bar was open, he would offer informal tours to visitors for 50 pesetas (roughly $.25). He also kept carp, chub, and gudgeon fish in a small circular pond in this area, a somewhat curious hobby as just across the street the Tajuña River provided renowned natural fishing spots, and nearby local fish farms featured rainbow trout.

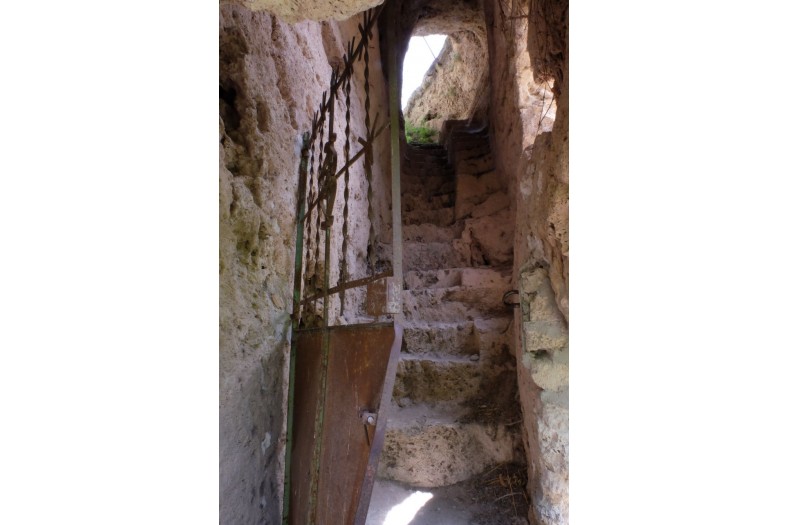

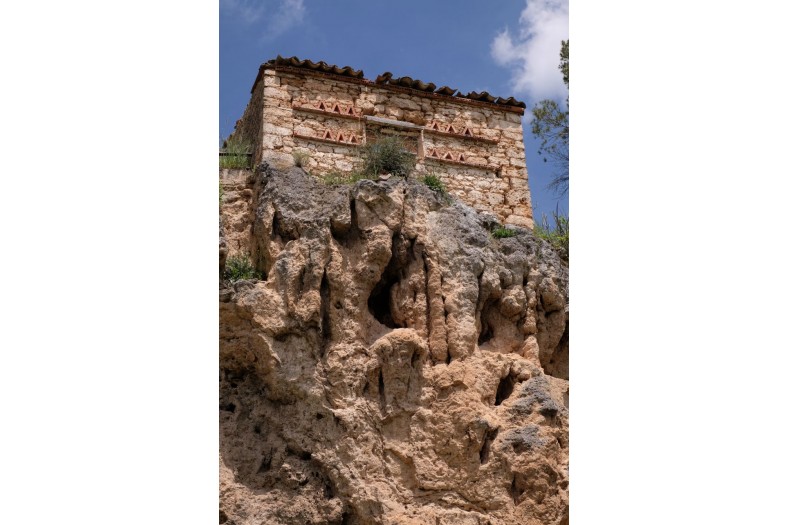

The compacted yet relatively soft volcanic tuff stone of this rocky hillside, a stone commonly used in construction, lent itself well to the elaboration of tunnels, grottoes, diagonal stairways, rows of openwork railings, and oval, low gothic, and keyhole arches. Built on innumerable levels, the natural cavities of the volcanic rock, heightened by natural erosion from wind and rain, both served to complement and obscure Pérez’s own excavations and additions, and, indeed, it appears that he took advantage of these recesses to design his own shelters, terraces, and caverns, all linked by narrow passageways, and all hacked out with simple picks and shovels. In addition, no small numbers of components were later added in cement. It is, however, unclear as to how much Pérez elaborated upon any pre-existing constructions, and whether he followed surviving models to develop the more convoluted and intricate complex whose ruins exist today.

As Pérez of course left no heirs, at his death the property in Cívica passed to his housekeeper in Valderrebollo, and then to her nephews. It has been for sale, but at present it seems to be in a state of limbo as well as a state of complete abandonment. Undergrowth and weeds are slowly covering the shaded areas, although the rock work on the hillside slope seems remarkably stable. While posted signs prohibit access, it is clear that they are honored only in their breach, as the sandy passageways within bear the signs of numerous footprints. Yet visitors honor the site; only an occasional cigarette butt mars the impression that this enigmatic site looked equally the same in centuries gone by, created by teams of devout workers driven by a mysterious yet compelling mission.

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2016

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, 19005

es

Latitude/Longitude: 40.6476021 / -3.1528692

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.