La Casa de Piedra (The House of Stone)Lino Bueno Utrilla (1848-June 24, 1935)

Threatened

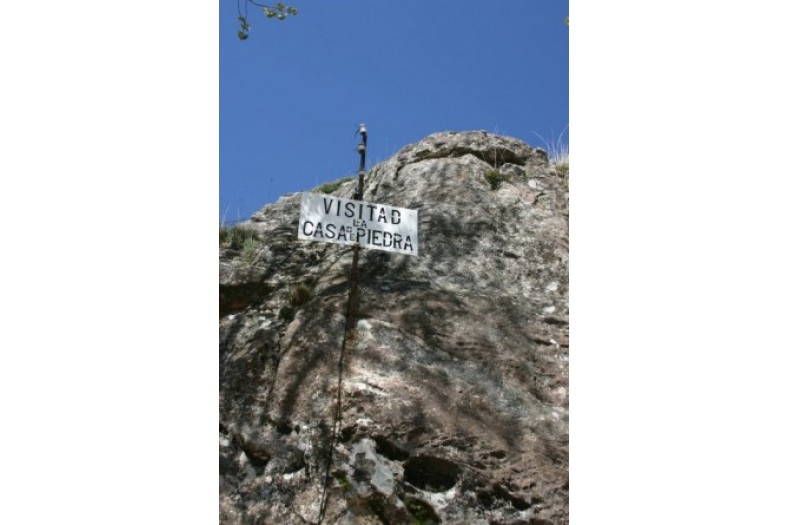

Alcolea del Pinar, Castile-La Mancha, 19260, Spain

Open to the public. A donation from visitors is requested.

About the Artist/Site

Bueno was born in the tiny village of Esteras de Medinaceli (with a current population of approximately forty residents), and had no schooling as a youth: there were few schools available in those days for poor village children. After his marriage to Cándida Archilla Martínez, born in the even smaller village of Ambrona, approximately eight miles northwest, they moved just south of Esteras to the much larger village of Alcolea del Pinar, with about 400 residents, in the hope of finding work. Due to his illiteracy and poor background, however, only manual labor was open to young Bueno, and he worked ten to twelve hours daily as a laborer on the roads, digging and maintaining ditches and irrigation channels, doing all manner of fieldwork, building walls, and even herding sheep. (In later years a resin industry was developed in which laborers with primitive tools tapped into the numerous pine trees—Alcolea’s namesake—in order to extract the resins, but this did not yet exist at the time that Bueno needed work.) He was a hard-working man, driven to do his job well, notwithstanding the menial quality of the labor, but he was never able to earn enough to save to buy a house of his own. Despite their meager income, he and Cándida had a large family of fifteen children, although they lost several at birth or at a young age.

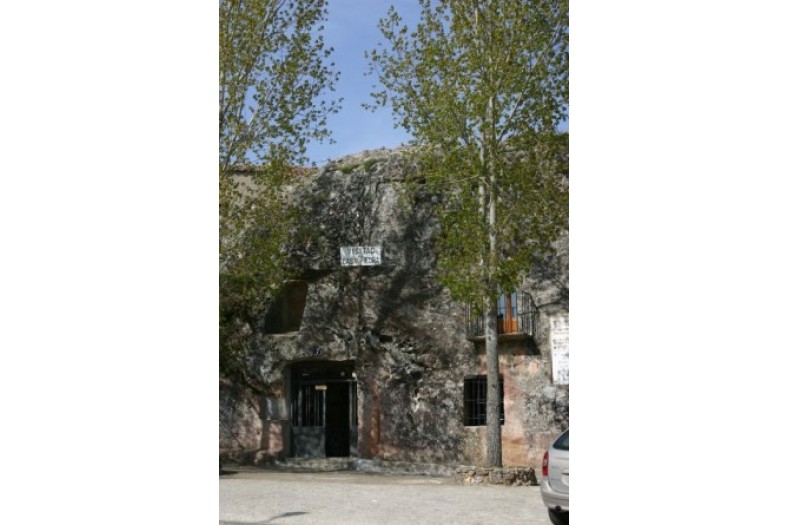

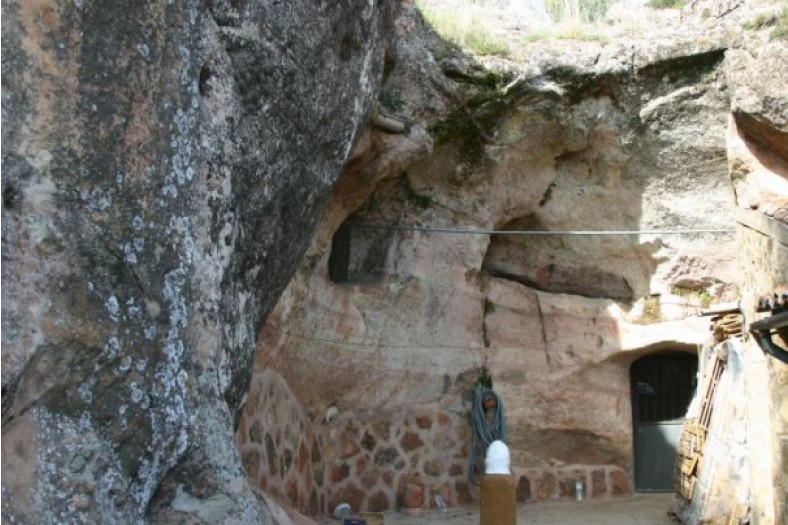

By 1907, at the age of 59—an age considered quite elderly in those days, particularly for those who had spent years doing manual labor—Bueno still had considerable energy, so he decided to ask the mayor of Alcolea for permission to carve into a massive boulder located at the outskirts of town in order to create a permanent and secure home for his family. He had passed this huge outcropping of granite with veins of sandstone every morning on the way out to work in the fields or on the roads, and it was solid; there were no fissures, apertures, or natural formations that might have given him the idea that he could easily hollow out living spaces within. At first he was rebuffed, but Bueno was so upset that the town council and mayor backpedaled, and although they believed that after he started working he would easily tire and abandon what they considered to be an outrageously preposterous idea, they told him that if he were to excavate it sufficiently to house his family, they would cede to him the rock and the property on which it was located. They did not, however, formalize the agreement in writing.

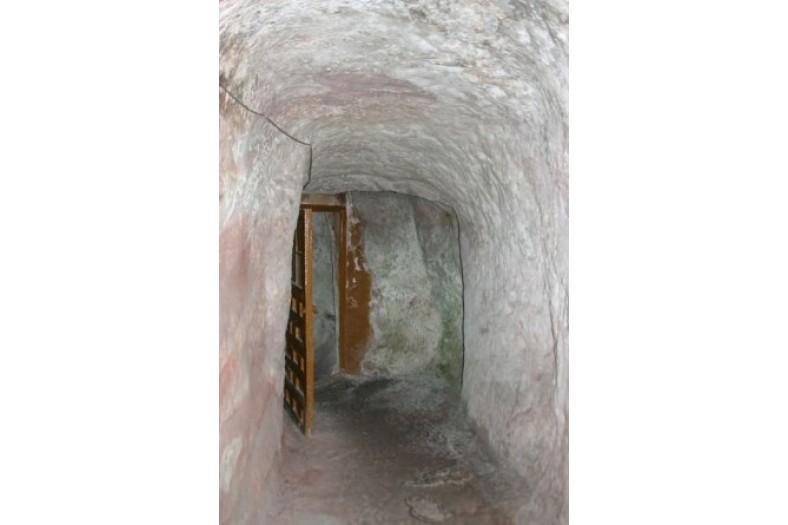

Bueno continued to work at his menial jobs from sunup to sunset, and then would work half the night picking and chiseling out an opening in the rock. He worked all his free hours as well, his wife helping him to clean up and toss out the dusty debris. At one point Bueno tried using dynamite, thinking that it would hasten the laborious excavation process, but the explosive created unwanted cracks in the rock, and he worried that he would be crushed by a cave-in, so he abandoned that idea, returning to his hand tools to hollow out the massive stone. By 1915, after eight years of hard labor, he had created a little passageway and one bedroom with two entrances from the exterior, and he, his wife, and his unmarried children moved into the house.

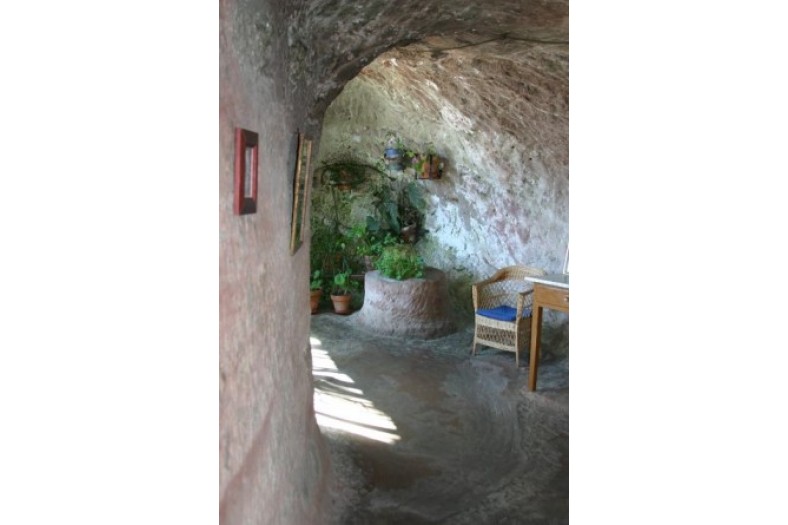

At this point Bueno went back to the town council and asked for the deed to the property, as he had been promised. Instead, they rebuffed him, reminding him that although there had been a verbal agreement, it had never been codified in writing and was therefore invalid. They did not try to evict him, however, so he continued to work, although he incessantly worried that he had no formal right to live there, and because the rock belonged to the property held by the town “in common,” he was afraid that he might someday be evicted, even after so many years of backbreaking work. He persevered nevertheless, ultimately excavating seven rooms and taking advantage of the veins or strata within the rock to create hallways and passages. His tools were rudimentary picks and small chisels; he wore out some thirty picks over the years, and the last one, broken and chipped, is treated almost as a reliquary by his family, as it so symbolizes the difficulty and the strength of his labor. It now hangs in honor on the wall of the entrance foyer.

Although Bueno continued working on the house, he asked a friend help him to write a letter to King Alfonso XIII explaining the circumstances and asking for his help. In the meantime (perhaps gleaning information about Bueno’s letter to the king), during a meeting in December 1920, the town council agreed to transfer ownership of the property to Bueno; however, despite this proclamation, the transfer was not finalized for another five years. It took even longer for the royal administration to review the issue of Bueno’s ownership of the Casa and, as presumably no follow-up letter was sent explaining that the situation had changed, on June 5, 1928 the king and Queen Vitoria Eugenia, grandparents of the current king, came to visit the house. Through his royal power the king conferred full title of the property to Bueno, so that he could pass it down to his children, and they to theirs, as an inheritance across the generations. The next year he was also awarded the bronze Medal for Meritorious Achievement for the tenacity and forcefulness of his years of labor. In 1978, fifty years after his grandparents visited the house, King Juan Carlos I and his wife Queen Sofia also visited the house, a notable distinction.

Until the night before he suddenly died in his sleep, Bueno worked on the house, and his two unmarried daughters continued living there until the last one died in 1990. Although the town has now renamed the street in front of the house in Lino Bueno’s honor, they provide no financial assistance, and it fell first to his children, and now his grandchildren, to turn the house into a small museum now open on a daily basis to the public. The house remains furnished in the style that Bueno and his wife effected, emulating any small house of the lower classes at that time, although it retains a somewhat more austere impression. A donation from visitors is requested.

Update Nov. 2017: The property is for sale. 7 rooms on three floors, with approximately 1076 square feet on the interior (100 square meters). The family is asking 1,500,000 Euros (roughly $1,761,000), but are open to all serious offers. In addition, there is a small piece of land above the Casa that could also be for sale. Interested parties should contact the artist’s great-great-granddaughter Amanda at angelwanda@hotmail.com

~Jo Farb Hernández, 2014

Contributors

Map & Site Information

Alcolea del Pinar, Castile-La Mancha, 19260

es

Latitude/Longitude: 41.0381144 / -2.475252

Nearby Environments

Post your comment

Comments

No one has commented on this page yet.